By Guest Columnist/cleveland.com on October 18, 2013 at 4:39 PM

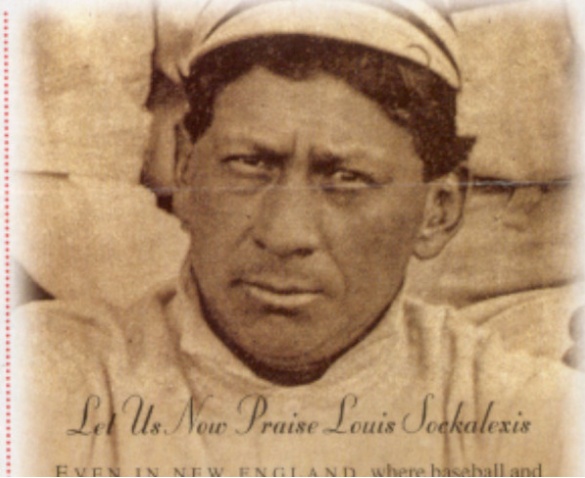

ORONO, MAINE — The Cleveland Indians organization has never had any real understanding — or appreciation — of what it has in the historical figure of Louis Sockalexis, a man who almost certainly broke professional baseball’s color barrier, a man who was definitively the first-known American Indian to play, a man who went through the exact same experience Jackie Robinson endured 50 years after him but never gets any comparable credit for doing so and a man who most certainly did inspire the team’s nickname.

I am the author of “Baseball’s First Indian,” a biography of Sockalexis I patiently cobbled together over the course of 18 years of part-time research and published in 2003. Perhaps even more significantly for Clevelanders, I’m the one who, in 1999, corrected the bevy of errors in the biography for Louis Sockalexis that annually appears in the Cleveland Indians Media Guide and received the gratitude of the team’s longtime Vice President for Public Affairs Bob DiBiasio. So, I’d like to exhort Clevelanders to recapture history and recapture their social consciousness.

Of course, Cleveland is far from alone in its disrespect. Sports Illustrated has published two error-riddled articles on Sockalexis over the past 40 years and still refuses to apologize for leaving him off a list celebrating Maine’s 50 greatest athletes when anyone with any sense of history would understand he belongs nearly at the very top. ESPN, too, failed to understand that he belongs on Maine’s Mount Rushmore of four greatest athletes, with only Joan Benoit Samuelson as an honest rival for such an honor.

And just when I didn’t think it could get any worse, I discovered the Cleveland-based Committee of 500 Years of Dignity and Resistance has at least two prominent members, including frequent spokesperson Ferne Clement, who appear to think of Sockalexis as only some second-rate athlete of virtually no importance who is merely the tool through which the hometown Major League franchise gets to use an inappropriate nickname and racist mascot.

C’mon, Cleveland, aren’t you better than this?

I am addressing these remarks in honor of that Cleveland where Carl B. Stokes became the first African-American mayor of a major U.S. city. And, earlier, that Cleveland where Larry Doby became the second African-American to play pro baseball, just 11 weeks after Jackie Robinson. And, even earlier, that Cleveland where Louis Francis Sockalexis, Penobscot Indian from the Indian Island reserve, Maine, was the sensation of professional baseball in 1897, featuring the skills of a five-tool player and a comparable charisma that earned him legendary status at any level he ever played.

Indeed, Sockalexis was one of those rarest of talents, an athlete held in awe by his fellow athletes who might be lucky to possess just one of his skills.

Thus, for me, the most contemptuous behavior occurring in Cleveland today is the Major League team’s present policy of “honoring” baseball’s first Native American player by featuring the flagrantly racist caricature, “Chief Wahoo,” and defending its continuation, citing tradition and popularity with fans.

First, this so-called “tradition” offers no tribute whatsoever to Sockalexis (who died in 1913) and only dates back to the late 1940s, when a young man sketched the crudest of American Indian images (some liken — fairly — the original caricature to the one Nazis used of Jews in their 1930s propaganda).

Secondly, the team’s condescending support of “low-brow” fans who proclaim the vile caricature “honors” American Indians, in order to continue merchandise sales, is the worst kind of pandering and is morally repugnant.

Pure and simple, Chief Wahoo is a vile caricature dating back to America’s institutionally-acceptable, racist past. Indeed, just think about it: Would the fans of the Los Angeles Dodgers accept it as a “tribute” to Jackie Robinson if team members were to suddenly don a Little Black Sambo-style caricature, featuring a cartoonish black figure, with kinky hair and large lips in baseball garb, wielding a bat or stealing home?

So, will it fall on Mark Shapiro, team president, to one day be remembered by his two children as the man who would not make a stand on behalf of a nation of Native Americans and hundreds of thousands of concerned members of other races looking to him to show some humanity?

Frankly, he needs only to acknowledge and join the stand presently being made by children and properly concerned school administrations in Ohio — and in every state around the country — to eliminate use of Native American mascots. Here, in my home state of Maine, there were over 30 schools that had Native American nicknames and mascots less than one decade ago; today, there are only three schools in the entire state still stubbornly resisting the moral winds of change.

Perhaps Cleveland needs its own Field of Dreams moment. No, I don’t mean long- dead ballplayers who come to play via a cornfield. I’m thinking someone, maybe a Justin Masterson, son of a minister, or, perhaps more appropriately, a player of color on the team, will suddenly allow his voice of conscience to proclaim, “No, I won’t wear this racist symbol.”

And then, maybe as well, the sacred — yes, this is a sacred practice — drumming of a culture will stop being mocked by a white man whose principal goal seems to be to annoy the opposition by engendering hatred for an action symbolizing a culture that has absolutely nothing to do with that culture.

Maybe we do need to look to our children and the next generation to beat a very different drum.

Fortunately, it has started. Schoolchildren all through the state of Ohio understand they should stop being demeaning to a race of people. When will the Cleveland Indians organization finally understand this?