By Ed Rice, Special to the Bangor Daily News

He was a college baseball player so legendary in his time that he was inducted into his school’s athletic hall of fame, even though he only attended two years. Then he broke a color barrier and became the first man of his race to play professional baseball. Then he became a professional baseball star, in spite of being subjected to the vilest of racial prejudice and violations of his civil rights from fellow players, fans and the press.

Without knowing any better, most, I’m sure, would think I was talking about Jackie Robinson.

But while most of the above is true of Robinson, I am, instead, talking about a man who is not a household name and, presently, is not appropriately recognized or properly celebrated in his hometown area and his home state.

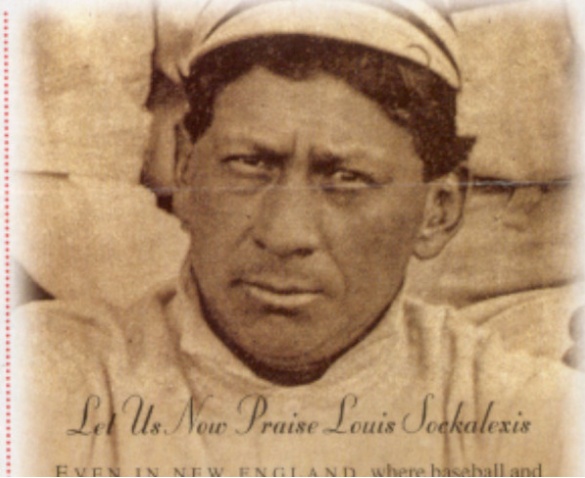

Louis Sockalexis, 1871-1913, Penobscot Indian from Indian Island, was the first known Native American to play professional baseball. He broke the “red” color barrier and was the first man of color to be allowed to play without other players boycotting and refusing to play against him.

He endured Jackie Robinson-like racial prejudice 50 years before Robinson broke the “black” barrier and paved the way for other great Native American players, including Hall of Famer Charlie Bender, John Meyers and the legendary Jim Thorpe.

Sockalexis inspired the nickname “Indians” for the Cleveland franchise in March 1897. Officially adopted in January of 1915, this year marks the 100th anniversary of the nickname.

Barely in his teenage years, Sockalexis was the terror of Maine’s popular summer “town baseball” leagues. While playing for the Warren team, Maine writer Gilbert Patten, who managed in that league, saw him. Patten later based his popular magazine baseball stories about the legendary fictional player “Frank Merriwell” of Yale on the incredibly skilled Sockalexis.

Sockalexis played two years at Holy Cross College, batting 0.444 and 0.436, and he is still among the college’s nine all-time greatest players. Following pro ball, even at age 35, Sockalexis still played for the Bangor team of the semi-professional Maine League with players more than a decade younger than him.

It is appalling to me that we have a nationally renowned Native American figure who stood at the forefront of a civil rights movement, and we continue to fail to show him any respect.

Cast in that light, we remain no better than Cleveland’s professional baseball team, which reduces him to a mere historical footnote so it can justify its use of an inappropriate nickname and racist caricature mascot. We’re no better than the insulting members of the Maine Sports Hall of Fame, created in the early 1970s, who failed to recognize Sockalexis until 1985 — by then it was as an “afterthought” because they’d inducted Louis’s second cousin, Olympic marathoner Andrew Sockalexis, in 1984. And we’re no better than the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, which still refuses to acknowledge Sockalexis’ pioneer status or apologize for the staff member who, in 1963, attempted to bestow this title on the “imposter,” James Madison Toy.

Since publishing my biography of Sockalexis in 2003, I have spoken at schools and libraries all over Maine. Frequently, I have said “Bangor has a statue dedicated to a mythic figure who did mythic things. One day I hope Bangor will build a statue to a real man who did mythic things.”

It is ironic to me to discover that Bangor is considering a proposal to build a fictitious “blue ox” to accompany our folk fable Paul Bunyan statue. Putting the outright silliness aside, let’s acknowledge that, considered side by side, a statue of a Native American baseball player and true historical figure will to leave us far prouder and attract many more visitors than an absurd myth stretched beyond reasonable presentation.

I have spoken to two prominent Maine sculptors, both of whom have expressed an interest in doing this project. One told me an 8-foot statue on a large base foundation, cast in bronze, would cost around $80,000. I am on the lookout for people who support this idea.

Back in the 1990s, USA Today identified 100 places in America where you should go if you are a baseball fan. There was only one place in Maine: Sockalexis’ gravesite on Indian Island, with its crossed bats and baseball on the plaque — donated in the 1930s largely by Holy Cross College. Almost every year I am contacted by some baseball fan from outside our state who is making the “pilgrimage” to pay tribute to Sockalexis.

So, yes, if we build this, they will come.