By Ed Rice, Special to the Bangor Daily News

As my plane winged its way to Cleveland last week, on my way to give a library talk in praise of Maine Penobscot Indian Louis Sockalexis and against the Cleveland Indians’ continuing use of Chief Wahoo, I began imagining myself as being something like the Jimmy Stewart character in “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.”

Upon my return trip to Bangor — after thinking about a solitary walk around Progressive Field that left me infuriated by the Cleveland Indians’ treatment of Sockalexis, followed by a prearranged luncheon meeting with two executives of the team’s public relations staff — I needed to ask myself whether that film title might more properly be characterized as “Sleeping with the Enemy.”

Today, I’m hoping it’s an appropriate mix of both.

As the author of the 2003 biography, “Baseball’s First Indian,” and writer of two commentaries on the controversy in the Cleveland Plain Dealer in the past 10 months, I received an invitation to speak at the Beachwood branch of the Cuyahoga County Library from librarian Margaret Reardon. Beachwood is an affluent, prominent suburb of Cleveland.

I went because I doubt anyone has ever gone to Cleveland to speak in honor of Louis Sockalexis, since he played as the first-known Native American major league baseball player in 1897 or since his death in 1913.

When it was learned I was coming to Cleveland to speak, Curtis Danburg, senior director of communications, emailed me to see whether I’d like to go to lunch with him and Robert DiBiasio, vice president of public affairs.

Because I was early for my luncheon meeting, I toured the ballpark, and just about everything I saw angered me. First, I stopped at the team shop. Nothing but a sea of Chief Wahoo images, from T-shirts to bobblehead dolls. And not one single item with the name “Sockalexis.” Just how does this team store “honor” Louis Sockalexis and the team’s identification with him? It doesn’t.

Then I walked around the ballpark. A beautiful statue of Bob Feller showed the young Iowa farmboy at the height of his skills, leg raised, about to fire an unhittable fastball. Inside the park, portraits of many of Cleveland’s greats stretched along a wall a whole section long in the upper deck, all featured in their glory days. Then I came to the portrait of Sockalexis, above a concession stand at one entrance to the park.

In 2003, when I last visited the park, the team was using a cutout of Sock from the Lowell, Massachusetts, team portrait, as a 1902 entry in the New England League. His weathered, worn-down face does not reflect vibrancy nor athleticism. So imagine my horror when I find the team actually replaced that portrait with a worse one.

It’s the old Penobscot postcard photo, the one taken a couple of years before his death, to capture a nickel from tourists coming to Indian Island, Maine. In the portrait, the old face of Sock, bloated from years of alcohol abuse, stares stoically forward, propped up in his old Cleveland uniform and cap.

Later, I would protest to Cleveland officials that you wouldn’t put a photo or a statue of Feller as an old man, long past his identity as a ballplayer or any of your other great players. Why are you doing this to Sock?

At that moment, clutching the gate that separated me from a closer inspection of the portraits along the concession walkway, I was the angriest I would be the entire trip. And, yes, far too theatrically, I yelled out at the portrait and to the spirit of Louis Sockalexis, a vow I intended to keep: I will do whatever I need to to get a better portrait up there as soon as possible.

The last indignity came in the reception room to the team’s executive offices. Paintings of Feller, Doby and Sockalexis adorn these walls. The painting of Sock had a background of the original Cleveland stadium, League Park, with Sock’s face ethereally depicted to its right. Again, it’s the old postcard face. However, the text accompanying the painting, provided by the team itself, was offensive. I was ready to confront these gentlemen on several counts, none of which had anything to do with Chief Wahoo.

At the meeting’s outset, when I smiled and asked what their “agenda” was, they said they merely wanted to “welcome” me back to the city and see if we had any “common ground” for discussion. I made it clear that the racist caricature and the inappropriate nickname are not negotiable for me.

But then came the surprise. They seemed willing to work with my requests to properly honor Louis Sockalexis. Understanding the team is facing national criticism and an awkward upcoming 100th anniversary next year, recognizing the official adoption of the team’s nickname, I saw my opportunity and seized it. With immediate results!

When I challenged the text to the painting in the reception room, Danburg accepted my reasoning and said it would be changed; indeed, several hours later, he sent me an email — with a photo — showing the amended text. He took off the racist-in- nature “Chief” Sockalexis and simply put “Louis Sockalexis.”

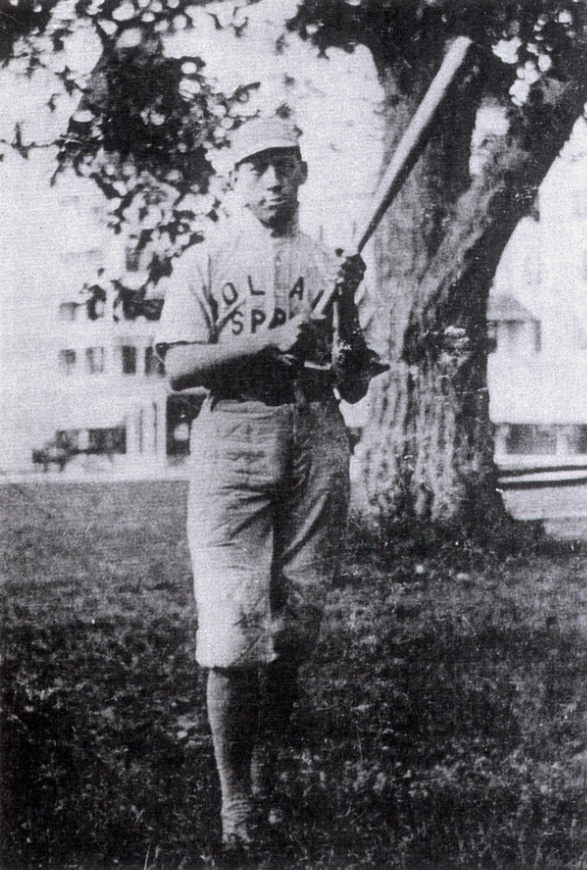

When I challenged the use of the portrait of Sock inside the stadium, Danburg said he had several choices of portraits of Sock to choose from, but he said he would happily accept and use a more fitting portrait. I suggested the full-figure one we use on the cover of my book, and he asked me to send him a copy of it. The first email I sent when I returned home was one to Danburg, with a digital picture attachment to the 1894 portrait of Sockalexis, in uniform and holding a bat, at Poland Springs.

The talk itself at the library attracted a nice audience of 40-45 members, and I spent the great majority of my speaking time focused on the respect and honor Louis Sockalexis deserves but does not get, through a detailed history of his life. Then I discussed the convoluted and frequently misinterpreted history of the nicknaming of the team. Finally, for just a few moments, I offered my reasons for condemning Chief Wahoo.

Prominent in my audience were Robert Roche, director of the American Indian Education Center of Cleveland, a Native American who became a “viral” celebrity when he was photographed during a confrontation with a fan in “redface” on opening day of the this year’s baseball season in Cleveland, and Zack Reed, an African-American member of the Cleveland City Council, who has vowed to continue the fight to force the Cleveland team to ditch Chief Wahoo. Roche filed a $9 billion lawsuit against the team, alleging it made this kind of money in profits from racist misuse of Native American images and symbols for over 100 years.

I told audience members I believe one day, soon, Chief Wahoo, will be terminated, and some day, off in the future, the inappropriate nickname too will come to an end.

Perhaps, trying to channel Jimmy Stewart-as- “Mr. Smith,” I boldly suggested a new Cleveland nickname could suddenly make the entire city proud, that a negative could be made into a positive. I offered the nickname “Rockers” to recognize the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the city’s identification with the earliest days of rock music. Couldn’t people just imagine a beautifully drawn caricature of a figure with a guitar-body, holding a bat or a glove, in spikes, with a ballcap-adorned playful head featuring an infectious grinning face that offends no one? Of course, people would buy the caps, T-shirts, sweatshirts, etc.

Crazy, I know, but like rock legend John Lennon once wrote, “You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.”