By Guest Columnist/cleveland.com on June 18, 2014 at 7:22 AM

Some day, probably under an entirely new ownership and new organizational leadership, I believe Cleveland’s baseball team will reverse course and demonstrate, like most of the rest of the country is currently doing with mascot and nickname changes, that there are far, far better ways to show respect to our Native Americans and their culture.

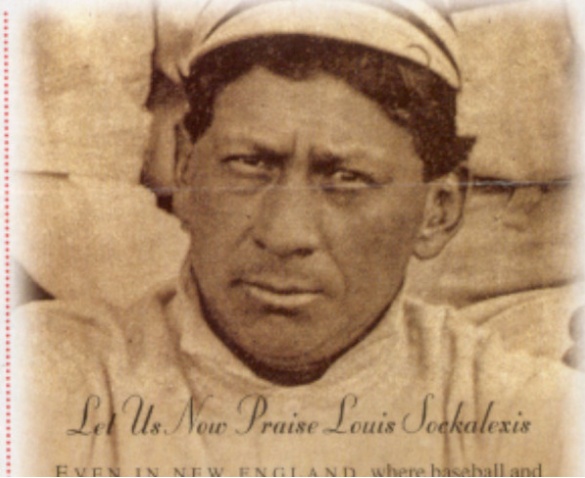

At that time, Clevelanders may demand a more attractive portrait of Louis Sockalexis at their stadium; perhaps, there will even be a movement to create a statue to recognize the member of Maine’s Penobscot tribe as the first- known Native American to play major league baseball, to show appreciation for the horrific racism he faced from peers, fans and the newspapers of the day, and to honor his role as the definitive inspiration for the nickname the team has used since 1915.

Sadly, it almost looks to me as if the Chief Wahoo logo actually has grown both LARGER and bolder on the caps and sleeves of this season’s Cleveland players, somewhat spitting in the face of the laudable Plain Dealer editorial to permanently retire it. That issue aside, I do think it is time for the people of Ohio to take longer, harder looks at the use of Native American nicknames and mascots throughout your state.

A little-known national website may hold a key to the explanation why the Dolan family and the Cleveland Indians organization are so comfortably allowed to continue their vile use of Louis Sockalexis to protect an objectionable nickname and a wholly racist mascot.

According to the website American Indian Sports Teams Mascots, at www.aistm.org, the state of Ohio is “champion” of all 50 states for no fewer than three different ignominious titles regarding use of Native American nicknames and mascots by its schools. Buckle up, Ohioians, and let’s take a look at them.

To begin with, Ohio ranks first for schools using Indian nicknames and mascots, with 219. The roll call of individual Ohio schools is right there on the website for your scrutiny. For comparison’s sake, rounding out the top 10 offending states are: 2. (tie) California & Texas, 181; 4. Illinois, 180; 5. New York, 161; 6. Oklahoma, 159; 7. Pennsylvania, 144; 8. Indiana, 112; 9. Georgia, 109; and 10. Missouri, 92.

Next, Ohio ranks first for total number of schools using the racial epithet “Redskins,” with a total of 22. Oklahoma ranks second here, with 15, and New York and Illinois are tied for third in this category, with 5.

Finally, and perhaps taking their cue from the professional team in Cleveland, Ohio ranks first for total number of schools using the nickname “Indians,” with 122 offenders. Texas is second, with 107, followed by New York, 105, and Illinois, 103.

And, yes, isn’t it obvious how hard it is to tell school kids this is wrong – and that many, many Native Americans all across our nation find this offensive – when the professional team in your own state is all but “celebrated” for doing it?

I am the author of “Baseball’s First Indian,” a biography of Sockalexis I wrote over the course of 18 years of part-time research that was published in 2003. I’m also the one who, in 1999, corrected the bevy of errors in the biography for Louis Sockalexis that annually appears in the “Cleveland Indians Media Guide” and received the gratitude of the team’s longtime vice president for public affairs, Bob DiBiasio.

One day it is my hope that Louis Francis Sockalexis, Penobscot Indian from the Indian Island reserve in central Maine, will receive proper tribute in Cleveland, where he was the sensation of professional baseball in 1897, featuring the skills of a five- tool player and a comparable charisma that earned him legendary status at any level he ever played.

Indeed, Sockalexis was one of those rarest of talents, an athlete held in awe by his fellow athletes who might be lucky to possess just one of his skills. He could: hit a baseball as far as any slugger of that day; hit safely as frequently as the league’s top high-average batters; make spectacular fielding plays using his exceptional speed; throw the ball prodigious distances with accuracy; be a base-stealing threat each and every time he reached base.

Sometimes the exceptional athlete whose career is tragically cut short, like a Herb Score or a Tony Conigliaro, is better remembered through the respect he received from his peers than by the numbers listed in a record book.

Cleveland can and will do better: I look forward to that day when I will return to Cleveland and see Louis Sockalexis properly recognized and honored by the professional baseball team of your city.