Maine Sunday Telegram Sunday, October 19, 2003

BOOK REVIEW: William David Barry

Story of baseball’s first Indian goes beyond diamond

Louis Francis Sockalexis (1871-1913), a Penobscot from Indian Island, Maine, burst into big league baseball in 1897. His extraordinary rookie year with the Cleveland ball club, then in the National League, led to the nicknames “Sock,” “Chief Sock-em” and “The Deerfoot of the Diamond.” He ended that season with a .338 batting average and created great expectations that would never be realized. Indeed, such baseball giants as John McGraw, Hughie Jennings and Maine’s own Bill Carrigan would remember him as one of the best players they ever saw.

Over the next two seasons, Sockalexis appeared sporadically for the Cleveland franchise. Subsequently, he drifted into the minors and ultimately back to Maine, obscurity and death in a Burlington logging camp. However, the legend of his athletic prowess grew to mythic proportions. Fans and fellow players never forgot his skills, never stopped talking about him and, ultimately, the Cleveland team would officially adopt the name “Indians” in his honor.

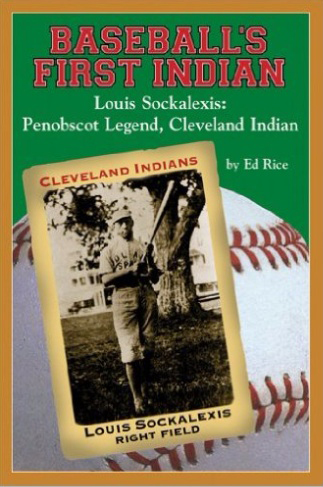

Yes, there will be those who will contest the last statement, but Ed Rice nicely sorts out that and other thorny issues in his new biography, “Baseball’s First Indian, Louis Sockalexis.”

It always seemed to me that Sockalexis, the man and the player, was doomed to loom large but indistinctly in the fog of lore. Rice changes all that with a lively, unpretentious work of historical detection. The book offers a solid bibliography and excellent footnotes that draw heavily on newspaper sports coverage. Rice’s close reading of these accounts opens a window on the player and his racially charged times.

What Rice does best is to stick to the facts and follow them to their logical conclusions. He confronts the assumption long held by a number of authorities, including the late dean of Maine sportscasters, Don MacWilliams, regarding the origin of the nickname “Cleveland Indians.” In “Yours in Sports” (Lewiston, 1969), the latter wrote: “The story that the Cleveland team changed its nickname from the ‘Spiders’ to the ‘Indians’ in honor of Sockalexis is not a true one, for the team had already taken on the latter appellation before the Maine Indian had been signed by the club.”

Sports journalists of the day called city clubs like Cleveland’s whatever took their fancy. In 1899 the Cleveland team played so poorly that they were routinely called the “Exiles” or “Misfits.” Rice discovered that the Indian “nickname emerged during the exhibition season of 1897, spurred by the presence of Sockalexis.” As late as 1907 Boston papers called Cleveland “the Indians.” Local Ohio papers referred to the team as the “Naps” after the great Napoleon Lajoie, but when he was traded to Philadelphia a new name was needed. The Cleveland Plain Dealer of Jan. 18, 1915, noted that the “revived” Indian designation harkened back to the great days of Sockalexis.

Another point concerns the claim by Luke Salisbury (author of the 1982 novel “The Cleveland Indian: The Legend of King Saturday”) that James Madison Toy (1858-1919) was the first American Indian in the big leagues. Rice states, “There is no evidence that Toy ever claimed Indian heritage while he was playing, and, indeed, there is no documented evidence to prove he had any Indian blood whatsoever.”

These points aside, the core of the book documents as clearly as possible Sockalexis’ youth in Maine, his father’s aversion to Louis’ career choice, the player’s extraordinary days at Holy Cross, his rise to the majors and instant fame. His first season, and especially the first half, was extraordinary, bringing adulation, money and an introduction to drinking.

As he became the center of attention, fans and foes focused on the fact that he was an Indian. In a time when political correctness was unknown, such treatment had sharp edges. Instant success, attitudes, coupled with injury and increased w=8.7dependence on alcohol, led to a rapid fall. To his credit, Rice takes the reader beyond the great season and follows Sockalexis through the minors (with some extraordinary success in 1902) and back to his home on the Penobscot. At last we have a solid, reliable account of one of Maine’s most fascinating sports figures.

William David Barry of Portland is a writer and historian.

Review From athomeplate.com

BASEBALL’S FIRST INDIAN: Louis Sockalexis: Penobscot Legend, Cleveland Indian

By Ed Rice Tide-Mark Press, 2003 $24.95 176 pp.

After years of being little more than a baseball trivia question (Who was the first Cleveland Indian), nineteenth-century outfielder Louis Sockalexis has become the subject of three major biographies within the past year. (we will be reviewing them all in upcoming weeks).

All three books are excellent giving the reader a glimpse into the rough-and-tumble world of early major league baseball, where players didn’t hesitate to trip each other with their spikes and many a game ended in fisticuffs and showers of rotten vegetables from the stands.

Maine author Ed Rice, born in Brookline and raised in Bangor, is a marathoner and journalist who has spent nearly two decades researching the Sockalexis story because he felt it was worth telling. Sadly, publishers weren’t interested until this year, causing his book to appear last on the list. “Baseball’s First Indian” details all the exciting play-by-plays of Sockalexis’s brilliant but too-short career. Handsome and easygoing, Louis Sockalexis became known as the nation’s best athlete during his two years at Holy Cross, where he excelled in baseball, football, and track. He posted batting averages of .436 and .444, and once made a throw from the outfield measured at 414 feet. In 1897 he was signed to the Cleveland team, then called the Spiders, and faced intense scrutiny from the press and fans, then known as “cranks.”

Fifty years before Jackie Robinson, Sockalexis broke the color barrier in major league baseball as the first acknowledged Indian player, and like Robinson, had to put up with endless racial taunting, stereotyping, and harassment from his fellow players. Unlike Robinson, Sockalexis lacked the toughness to withstand the pressure. Although there is evidence of his drinking in college, it destroyed his hot hitting and fielding after only four months in Cleveland, and his career sputtered to a halt. He played fractions of the 1898 and 1899 seasons before being released to the minor leagues, where he drank himself from one team after another. Nonetheless, he occasionally showed flashes of his old dazzling speed and he never lost his powerful throwing and hitting. He managed to play a solid, complete season with the Lowell team before returning home to Indian Island, Maine, where he coached Penobscot youths, eventually sending five of them to the New England league.

As a fellow Mainer, Rice is able to offer a local angle, enriching his story with interviews with those who knew “Sock” (“the nicest man I ever met,” says one) and recount colorful anecdotes such as Sockalexis throwing a ball across the Penobscot River on a bet, and tricking a runner with a baseball hidden in a secret pocket. His wild carousing days apparently behind him, he even sang in his church choir. Respected as an umpire and well loved by his family and tribesmen, Louis Sockalexis operated the island ferry and worked as a logger in the Maine woods until his death in 1913 at the age of 42.

Rice also examines the controversy over the Cleveland Indians’ Chief Wahoo mascot, and their dubious claim that they took their current name in honor of Sockalexis. He is able to demonstrate that while this was mostly a PR stunt in keeping with the custom of naming teams after Indians (Boston Braves, for example), the fact that they had some of their finest moments during the rookie year of Louis Sockalexis suggests that he was indeed the inspiration for the name. We also have Rice to thank for the induction of both Louis Sockalexis and his second cousin, marathoner Andrew Sockalexis, into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame in 2000.

This is a fascinating and extensively researched book, well worth the wait!

Give this one 3 out of 4 balls and call it well worth the read.

Reviews from Amazon.com

Baseball’s First Indian, Louis Sockalexis: Penobscot Legend, Cleveland Indian

by Ed Rice

Take This One Home!, September 18, 2003

Reviewer: A reader from Brighton, Massachusetts United States

This new book by Ed Rice has everything–stats, rare photos of Louis Sockalexis and Hall-of-Famers such as “Cy” Young and Jesse Burkett, and game-by-game summaries. It brings to life the rough-and-tumble life of nineteenth-century baseball, and gives a glimpse into “Sock’s” later years, showing that he was admired by all who knew him. His fellow tribesmen honor him to this day as a great athlete. This is a great read going into the postseason!

This Book’s a Home Run!, September 1, 2003

Reviewer: An Amazon.com Customer

This is the story of Louis Sockalexis, the first Indian ballplayer who had a great college career but fizzled out in the majors. Maine author Ed Rice tells us all about this player who became a national sensation in one short season. This exciting bio is crammed with baseball lore and play-by plays of Sockalexis’s games with Holy Cross and the early Cleveland Indians.

Without TV or radio, the fans had to imagine Sock’s sizzling throws to the plate from deep right field and hot line drives. He was so fast he could steal bases at will. He had to face war whoops and taunting crowds, but like Jackie Robinson, he just quietly played the game. Sadly, drinking cut his career short but he holds a special place in baseball history as a pioneer and great player who could have become a champion if he’d lasted long enough. This book makes great reading during baseball season!

This One’s a Hit!, August 16, 2003

Reviewer: swstroshane (see more about me) from Brighton, Massachusetts United States This has been a remarkable year for books about Louis Sockalexis, the long-forgotten nineteenth century Penobscot outfielder. When he was signed with the Cleveland national team, he became the first Indian to play in the major leagues.

This book by Maine author Ed Rice tells Sock’s story from a local point of view as well as extensively covering his outstanding career at Holy Cross and games with Cleveland, before drink and injury destroyed his career.

Sockalexis broke the color barrier fifty years before Jackie Robinson, but his love of the high life and the overwhelming pressures of racism led him astray.

Mr. Rice’s book is lavishly illustrated and vividly recreates the rough-and-tumble world of nineteenth-century baseball. The author also describes Sock’s career in the minors, where he played better than people think, and his final years on Indian Island as a well-respected baseball coach and umpire.

This is a great piece of Americana and a must-read for baseball fans everywhere!

A Baseball Pioneer, August 12, 2003

Reviewer: A reader from Brighton, Massachusetts United States For years, Louis Sockalexis wasn’t much more than a trivia question: who were the Cleveland Indians named for? Now there are THREE new books about him.

“Sock” was an outstanding athlete in his time and showed great promise. If drink hadn’t ruined his major league career, he could have ranked as one of the all-time greats. Still, he deserves to be remembered as a baseball pioneer, the first Native American player not long after the Wild West was still killing off Indians. He had to put up with rough treatment from the crowds, but it didn’t seem to bother him. In fact, he was well-liked by nearly everyone–too much, sad to say. Everyone wanted to buy him a round, and he loved to party. Finally, a foot injury wrecked his playing for good.

Ed Rice, a Maine author, includes a nice local view of Sockalexis’s later life and interviews with people who knew him. There are fond memories and funny anecdotes about Sock, who never lost his ability to throw like a cannon or hit the ball out of the park. He coached a Penobscot team and sent five players to the New England leagues. He was such a good umpire you didn’t dare argue with him. His last years were quiet but he always kept up with the latest news on baseball. They say when he died, he had clippings from his magical rookie year in his pocket. He’s buried on Indian Island near Bangor, Maine, where fellow Mainers and visitors from all over can pay their respects to “Baseball’s First Indian.”

This is an outstanding book–I give it two thumbs up!

An Angel in the Outfield, August 12, 2003

Reviewer: A reader from Brighton, Massachusetts United States For part of one magical season in 1897, Louis Sockalexis, “Baseball’s First Indian,” had wings on his feet in the outfield. The fastest runner in the country, he ran down line drives and made spectacular diving catches followed by bullet-like throws to the plate. He went on a hot hitting streak that seemed unstoppable. Though he was showered with racial abuse at first, he soon won over the crowds with his calm demeanor and easy smile.

It helped that he was rugged and handsome. If only the magic had lasted!

Louis had an alcohol addiction that soon made itself known. It wrecked his career when he injured himself and lost his lightning-quick speed and reflexes. The Cleveland Spiders (now Indians) gave him several chances to shape up, but he couldn’t stop drinking.

Finally they let him go in 1899.

He drank himself off several minor league teams as well but occasionally showed flashes of his former brilliance. He played one complete season with the Lowell Tigers, posting a .288 average. In 1902 he went home to Indian Island for good. He quit drinking and won respect as an umpire and coach for Penobscot youths who were proud to learn from the best.

Of the three new books on Sockalexis, this one by Ed Rice is the most complete, covering each game of “Sock’s” career and giving us a close look at his last years among his tribesmen, who honor his memory to this day. Mr. Rice grew up in Maine with the legend of Sockalexis close by, and decided many years ago his story was worth telling. This book is a remarkable portrait of a gifted ballplayer who’s finally getting the attention he deserves.

A New Baseball Classic, August 7, 2003

Reviewer: A reader from Brighton, Massachusetts United States Who remembers Louis Sockalexis, who played right field for the Cleveland Indians way back when they were called the Spiders? Ed Rice remembers and tells us all about this player who became a national sensation in one short season. This exciting bio is crammed with baseball lore and play-by plays of Sock’s games with Holy Cross and the Cleveland team. Sockalexis sparked such excitement on the field with his outstanding playing that sportswriters started calling the whole team the Indians. Crowds who jeered at him and mocked him with war whoops quickly cheered when they saw him throw runners out at the plate and pound out hits. He was so fast he could steal bases standing up.

Sockalexis was a handsome and popular guy, a big favorite with the women. He played like a superman until too much drinking destroyed his career. A few minor league teams let him play but he mostly drank too much with them too. Sometimes he played well and gave the small crowds a glimpse of what he used to be. Then he went home to Indian Island for the rest of his life.

He became a coach and eagle-eyed umpire for the Maine leagues, which means he probably quit drinking.

Louis Sockalexis holds a special place in baseball history as a pioneer and great player who could have become a champion if he’d lasted long enough.

This book belongs in every library!

Chief Wahoo He Ain’t!, August 7, 2003

Reviewer: A reader from Brighton, Massachusetts United States On the cover of Ed Rice’s new book, a handsome, serious young player stands in full uniform, holding his bat and looking ready to whack the ball out of the park. No feathers, no big nose, no huge buck-toothed grin, and his skin isn’t fire-engine red. That’s because he’s no cartoon Indian, he’s a real person. He’s Louis Sockalexis, rightfielder, with an arm like a rifle and the fastest feet in the country. The Cleveland Indians may be named after him but their mascot has nothing to do with Sockalexis.

Sockalexis broke the color barrier in baseball in 1897 as the first Indian ballplayer. At first crowds booed him and made silly war-whoops, but when they saw his spectacular diving catches, home runs, and deadly accurate throws to the plate, their jeers turned to cheers. Soon he had many admirers–too many, sad to say. He drank too much, got careless, and hurt himself, wrecking his speed and reflexes for good.

Mr. Rice tells us all about “Sock’s” last years after he went home to Maine. Louis quit drinking and taught his secret baseball tricks to the young players of his tribe. Five of them went to the New England Leagues and batted over .300, just like their coach. Sockalexis became known as a fair umpire for local games, and sometimes he would amaze people with his throwing skills. He had many loyal friends, and even today the Penobscot people are proud to tell visitors about their great ballplayer.

I give this book four stars!

A Fitting Tribute to the Man and the Legend, August 6, 2003

Reviewer: swstroshane (see more about me) from Brighton, Massachusetts United States Although “Baseball’s First Indian” is the third Sockalexis book to appear in the past year, Ed Rice actually started this well-researched biography nearly 20 years ago. His book offers stats galore as well as an interesting account of Sock’s later years in the minors, where he played better than most people think, despite his drinking.

I especially liked the warm-hearted portrait of Sock’s final years on Indian Island, where he was an extremely popular coach, umpire, and community member. He even sang beautifully in the church choir! Though he will always be remembered as one of baseball’s tragic figures, he was more than that to his Penobscot family and tribesmen–a model of dignity, grace and generosity to the end. A fitting tribute by a Maine author to a fellow Mainer!